Idea

In the summer of 1732, the Swedish medical student Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) travelled through Northern Scandinavia. His diary of that journey has been celebrated as pioneering modern scientific and ethnographic fieldwork. We propose to read it against the grain. The knowledge Linnaeus gathered was generated “in transit” at intersections of diverse communities and affected by frameworks of hospitality and hostility.

Our vision is to co-produce a critical online edition of the diary with academic and non-academic experts in Lapland while re-tracking the journey. Re-translating and re-tracking the journey would work in tandem as catalysts for critical, creative and experimental discourses on wider issues of contemporary relevance ranging from sustainability and wellbeing to indigeneity and sovereignty. By transposing Linnaeus’s methodology into the present, we intend to refocus the archival lens and question the formation and authority of scientific knowledge.

Together, we want to address questions such as: How did an insect-borne disease known to reindeer herders as curbma end up in Carl Linnaeus’s Systema naturae (1758) as a fly-species named Oestrus tarandi? In what ways did Linnaeus integrate within his cosmology lessons learned from Finnish settler-women about easing after-pains in childbirth by drinking umbilical blood? What do such translations reveal about the role of encounters, mobility and multilingualism in the generation of global knowledge? Do they simply consist of extracting and appropriating local knowledges? Or are they intrinsically shaped by the potential for empathy, curiosity and aversion that cross-cultural encounters provoke?

We are grateful to the British Academy and Leverhulme Trust for financial support through their Small Research Grants funding scheme that allowed us, together with Megan Woolley, to compile an electronic database and map of the route of Linnaeus's journey, carry out some fieldwork and meetings with potential collaborators in Lapland during the late summer of 2019, and organize a workshop at the end of the year to put together a larger grant application for the full project. We would also like to thank the Linnean Society of London (UK), the Arctic Centre at the University of Lapland, Rovaniemi (Finland), and Vaartoe Centre for Sami Research at University of Umeå (Sweden) for the support they provided. Very special thanks are due to Michel Durnix for the design of this website and Ludger Müller-Wille.

Background

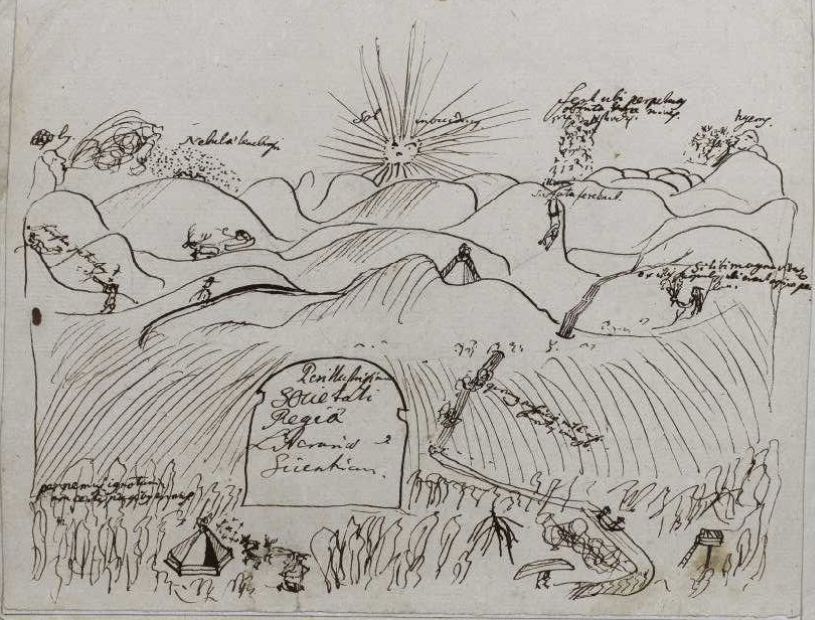

During his trip, Linnaeus composed a travel diary that exalted the life-style of Sámi reindeer herders and described the natural resources of Northern Scandinavia. Linnaeus has been hailed as a pioneer of modern ethnographic and ecological fieldwork, demonstrating a keen eye for interactions between people, places and organisms. While the diary itself was not published during the lifetime of Linnaeus, inclusion of passages from it in publications like Flora lapponica (1737) impacted on enlightenment discourses of the "noble savage." Extracts from the diary were first published in English translation in 1811 by James Edward Smith, President of the Linnean Society of London, which still holds the original manuscript. Scholarly editions of the Swedish-Latin text followed in 1889, 1913 and 2003. In addition, there are French, Dutch, German and Finnish popular translations as well as another English translation in 1995, which follows Smith’s redactions. Linnaeus's journal thus continued to fuel the imagination of nineteenth and twentieth-century scientists, writers and artists, resulting in an image of the land as inherently healthy and magical, yet also cold and dark in the winter, and full of insects during the short summer.

Accessible online at http://linnean-online.org/157546/.

The journey and its stories are tools that have been used for millennia to conquer nature and people. Linnaeus engaged no less in the global making of places, bodies and selves. To find out about the potential of the land for food, ores, and other economic goods he objectified Lapland in a proto-colonial manner. While in later reports and publications Linnaeus created an image of Lapland as a stagnant and desolate region, waiting to be explored and exploited, his diary documents how people there knew very well how to make a living, and were the ones on whose expertise and hospitality he depended. A closer reading of his journal reveals his reliance on multiple actors who also moved across cultural and political borders, usually were multilingual, and helped him find his way and acquire knowledge. Passports asking for safe passage and assistance, along with carefully drawn-up lists of hosts and gifts received or given, are preserved among Linnaeus's manuscripts. They reveal the contours of the social, political and ethnic landscapes he travelled across.

Moreover, Linnaeus was far from being the first to report from Lapland. Travellers from the South had reached the North long before Linnaeus, and Northerners had long been travelling to the South. Scholarly interest in Lapland had been intense, and the Swedish crown had been sponsoring its exploration by antiquarians and geographers since the sixteenth century, culminating in Olaus Rudbeck's infusion of the region and its traditions with classical myth. Linnaeus deliberately sought out landmarks and antiquities familiar from this literature, and many of these remain attractions for tourists and other travellers to this day. The sights and facts locals point to in order to impress visitors constitute a cultural repertoire of astonishing historical durability. It formed a kind of infrastructure for Linnaeus to navigate the boundary between the known and unknown. One can therefore say that Linnaeus was on a guided tour, in the sense of using prior texts to navigate Lapland and of being guided by local informants.

Approach

To bring out these aspects and “decolonize” the image of Lapland to which Linnaeus himself contributed, we envisage a new methodology designed to read sources against the grain and to foster contemporary discourse of how knowledge is generated “in transit” at intersections of diverse communities. The methodology would rest on two intertwined elements: a new English online critical edition of the diary and associated manuscripts; and a journey along the route Linnaeus took that would facilitate co-production of the on-line edition at local gatherings with academic and non-academic experts. The edition would not only present an English translation with commentary alongside transcriptions and facsimiles of the Swedish-Latin original but also provide a platform for discursive elements, such as records from gatherings and other events arising from the journey (exhibitions; artistic, literary or political creations), or blog-space for comments by individuals with special expertise: scholars, scientists and museum curators, poets and artists, amateur naturalists and historians, stakeholders of various kinds (e.g. representatives of local residents, indigenous rights activists, environmentalists), or health professionals and local business representatives.

Re-translating and “re-tracking” the journey would work in tandem as catalysts for critical and creative discourses on wider issues of contemporary relevance ranging from sustainability and wellbeing to indigeneity and sovereignty. We thus envisage a methodology that is clearly distinct from "historical re-enactment." Instead of recreating the past, it transposes the kind of interactions that shaped the historic journey into the twenty-first century, analogous to the current trend of "re-working" recipes and experiments in the history of early modern crafts and experimental sciences. To our knowledge, our project would be the first to adapt this methodology for the purpose of understanding the conditions and consequences of scientific travel rather than experiment.

Who we are: Staffan

Staffan Müller-Wille is a historian and philosopher of science focussing on the production of biomedical knowledge as a geographically, socially, and culturally distributed process. He is particularly interested in "paper technologies" scientists use to record their observations. Linnaeus's manuscripts reveal how he experimented throughout his career with a number of paper-based information tools – lists, tables, book annotation, index cards – in order to collect and integrate data about plants and their medical uses. More recently, Müller-Wille has become interested in classic works in the history of science and medicine online, presenting, for example, a new translation of Gregor Mendel's paper on heredity in peas.

For more information and other publications, visit his home page.

Who we are: Elena

Elena Isayev is an ancient historian who has been developing the journey as a discursive tool. As a historian and practitioner, she is focusing on migration, hospitality and exceptional politics in contexts of displacement. Investigations drawing on ancient contexts and material remains address dichotomies of public and common space, counter-cartographies and relational approaches to place. She also works with Campus in Camps in Palestine and is a member of UNDRR/ICCROM expert panel on the role of traditional knowledge systems in disaster risk reduction. Currently, she is leading the team of Imagining Futures through Un/Archived Pasts, funded by an AHRC/GCRF Network+ grant.

For more information and other publications, click here.

Encounters and Links

March 2021: Staffan presented on Linnaeus's thoughts about the use of trees in Lapland at the Alan Turing Institute & University of Exeter workshop "Towards Responsible Plant Data Linkage: Global Challenges for Food Security and Governance".

November 2020: The Linnean Society of London launches L: 50 Objects, Stories and Discoveries from the Linnean Society of London, showcasing "treasures" in the Society's collections. We contributed a chapter on Linnaeus's Lapland diary to this lavishly illustrated volume.

September 2020: Due to Covid-19 it was not possible to cross into Norway over the mountains from Padjelanta (as Linnaeus had done). Hence, Staffan and Elena presented results from their latest trip "virtually" in the Science Studies Colloquium Series of the University of Oslo.

September 2020:In a letter to Jim Secord we reflect on how our experiences during the latest field trip to Padjelanta National Park can be used to take his concept of "knowledge in transit" further. The letter was included in a collection to mark Jim's retirement that was put together by Sadiah Qureshi and Sujit Sivasundaram under the title Secord in Transit: A Natural History of this Most Extraordinary Human As Told by Witnesses and Secretly Collected by the Editors.

August 2020: The Covid-19 pandemic brought activities to a halt in the spring of 2020, but we were able to use the moment of reprieve during the summer for a second field trip. It took us to Padjelanta/Badjelánnda National Park, where Linnaeus spent some time with Sámi reindeer herders, and where we were to meet a potential collaborator, Katarina Parfa Koskinen. We walked from Kvikkjokk to Staloluokta in the mountains following a well-marked hiking trail. On the way back to Kvikkjokk, we traced the original, rather tortuous route along which guides took Linnaeus in 1732.

November 2019: We organized a proof-of-concept event with collaborators in Boden, a late nineteenth century garrison town in Norrbotten county. The event was hosted by the art gallery Havremagasinet. For a program and short summary of key themes click here.

August/September 2019: We went on a field trip to hold workshops with potential collaborators – which included reading sections of Linnaeus’s journal together –and to re-track bits of Linnaeus’s journey along the Finnish Baltic Coast and the rivers Umeälven and Luleälven in Sweden. Our journey took us from Rovaniemi, through Oulu and Helsinki to Tallinn in Estonia, from Tallinn to Stockholm and Uppsala, from Uppsala to Umeå, and then on a round-trip through Lapland, stopping over in Lycksele, Arjeplog, Jokkmokk and Luleå. For an account of some of the people we met, places we visited, and things we learned, click here.

June 2019: Staffan reminisces about his 2016 trip in a chapter contributed to Surprise: 107 Variations on the Unexpected, a volume put together by Mechthild Fend, Anke te Heesen, Christine von Oertzen and Fernando Vidal to honour the Lorraine Daston's creativity and generosity as Director of Department II of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

April 2019: Staffan gave two presentations on Linnaeus in Lapland, one at a workshop organized in the context of Maria Roos's and Vera Keller's project "Collective Wisdom: Collecting in the Early Modern Academy", and another at the Forschungszentrum Gotha, where he met with Bernhard Schirg who is keenly interested in early modern perceptions of Lapland.

March 2019: Staffan explored Linnaeus's narrative strategies and how they intersect with his taxonomic gaze in the Narrative Science seminar series at the London School of Economics. Scroll down the blog page, and find him introducing Claude Lévi-Strauss's concept of bricolage as an analytic tool to understand Linnaeus.

February 2019: Elena and Staffan talked to a mixed crowd of philosophers, biologists, sociologists, anthropologists, historians and literary scholars in the Egenis seminars series at the University of Exeter. Subjects we explored included hospitality, parasitism, life-cycles, alternative spaces and travel as a method to bridge time and space.

November 2018: Staffan and Elena met Jonas Monié Nordin and Carl-Gösta Ojala at Uppsala University to learn about their research project Collecting Sápmi. Early modern globalization of Sámi material culture and Sámi cultural heritage today.

October 2018: Sandi Hillal invited Staffan and Elena to exchange ideas about travel and hospitality at ArkDes museum in Stockholm as part of her Al Madafah/The Living Room project.

June 2018: Staffan and Elena presented the project idea at the SLSAeu Green Conference in Copenhagen.

May 2018: Staffan and Elena went on a one-week trip to discuss the project with colleagues in Sweden and Finland. The journey began in Rovaniemi. Anthropologist Nuccio Mazullo had organized a research seminar at the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland to showcase our ideas. From Rovaniemi, we drove to Umeå, where Isabelle Brännlund brought us together with colleagues at the Centre for Sami Research — Vartoe in Umeå. Per Ramqvist made room for us in his summerhouse near Örnsköldsvik, and sang the praises of Höga Kusten's past and present. On our way to Umeå, we also passed through Boden. Ibrahim Muhammad Haj Abdullah and Yasmeen Mahmoud greeted us there with warm hospitality, and we also visited the art gallery Havremagasinet.

May 2018: Staffan presented the project in the seminar series of the Institute for History of Science and Ideas at Uppsala University.

April 2018: Staffan met with artist Åsa Sonjasdotter at the Linnean Society of London to study Linnaeus's travel journals. Åsa is carrying out research on the history of cultivated plants as part of her Artistic Research Residency with the Baltic Art Centre.

December 2016: Staffan presented on Linnaeus at the annual meeting of Svenska Linné-Sällskapet (Swedish Linnaean Society).

June/July 2016: Staffan undertook a one-week trip to Padjelanta and Tornedalen with artist James Prosek, ornithologist Krzystof Zyskowski and PR-strategist and writer Håkan Stenlund. James wrote a nice article in the New York Times about this trip.

Readings

Andersson Burnett L, 2013. “Selling the Sami?: Nordic Stereotypes and Participatory Media in Georgian Britain.” In Communicating the North, ed. Harvard J, Stadius P, 171-96.

Bilak D, Boulboullé J, Klein J, Smith PH, 2016. “The Making and Knowing Project.” West 86th 23: 35–55.

Broberg G, 2003. "Varför reser Linné? Varför springer samen?" In Så varför reser Linné?, ed. Jacobsson R, 19-52.

Clifford J, 1997. Routes: Travel And Translation in the Late Twentieth Century.

Dietz B (Ed.), 2016. Translating and Translations in the History of Science. Special Issue of Annals of Science, Vol. 73, Iss. 2.

Fors H, Principe LM, Sibum H-O, 2016. “From the Library to the Laboratory and Back Again: Experiment as a Tool for Historians of Science.” Ambix 63: 85-97.

Hansson H, Lundström J-E, 2008. "Introduction: Lapland in London and Lapland and Elsewhere." In Looking North, ed. Heidi Hansson H, Lundström J-E, 5-24.

Ingold T, 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description.

Ingold T, Vergunst JL (eds.), 2008. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot.

Kelly AH, Geissler PW, 2016. "Field Station as Stage: Re-Enacting Scientific Work and Life in Amani, Tanzania." Social Studies of Science 46: 912-37.

Koerner L, 1999. Linnaeus: Nature and Nation.

Outram D, 1999. “On Being Perseus: New Knowledge, Dislocation, and Enlightenment Exploration.” In Geography and Enlightenment, ed. Livingstone D, Withers CW, 281-94.

Pratt ML, 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation.

Secord JA, 2004. “Knowledge in Transit.” Isis 95: 654-72.

Stoler AL, 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense.

Sydow C-O, 1978 "Linné och de Lyckliga Lapparna?: Primitivitiska drag i Linnés Lapplandsuppfattning." In Utur stubbotan rot, ed. Granit R, 72-78.

Wagner F, 2004. Die Entdeckung Lapplands: Die Forschungsreisen Carl von Linnés und Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis’ in den 1730er Jahren.

Zorgdrager N, 2008. Linnaeus as Ethnographer of Sami Culture. Tijdschrift voor Skandinavistiek 29: 45-76.